The story started over 200 years ago…

1797

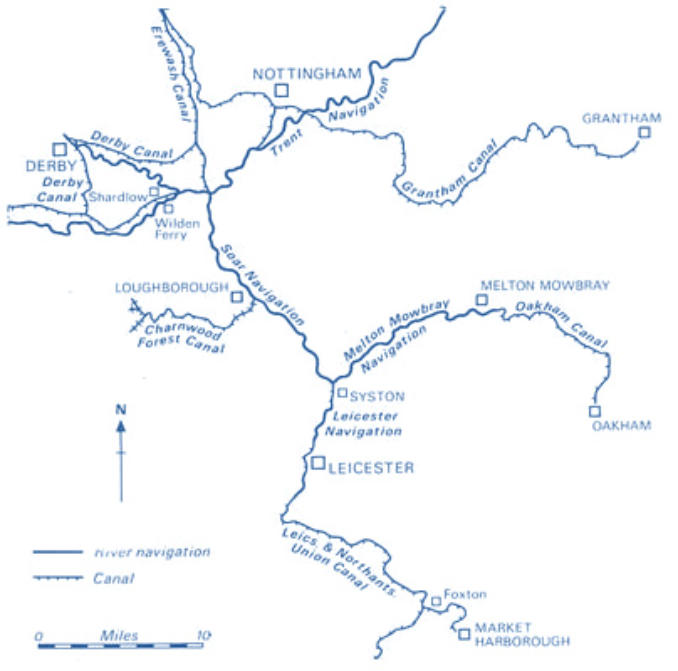

The 1790s was a period of “canal mania”. Towns everywhere saw a new waterway as the key to increased trade and future prosperity, while speculators recognised the dividends to be reaped from prosperous navigation companies. Leicestershire was no exception. In 1778 the River Soar opened from Trent Lock, near Nottingham, to Loughborough. The immediate calls to continue the line to Leicester were followed shortly afterwards by suggestions that Melton Mowbray should also be included in the scheme.

After various routes had been rejected in favour of a fairly simple canalisation of the River Wreake, a tributary of the Soar meeting the larger river at Cossington, the newly independent “Melton Mowbray Navigation” finally received parliamentary approval in 1791. Despite the exorbitant demands of local landowners necessitating a major refinancing halfway through construction, the navigation was opened all the way to Melton Mowbray in 1797 at a cost of just over £40,000.

The canalised Wreake was never as profitable an undertaking as the nearby Soar Navigation, but Melton’s appetite for Derbyshire coal ensured that enough boats would pass down the Melton Mowbray Navigation (paying tolls in the process) to secure its financial viability. Six years later, this traffic would almost double as 15 more miles of navigable waterway were opened.

The canal mania of the 1790s was by no means a phenomenon unique to Leicestershire: it was a nationwide craze, and the citizens of Oakham, Link to a copy of a page from The London Gazette (1845).

1874

Just as the 1790s had seen national enthusiasm for canals, the 1840s were to see the start of a national craze for railway-building. Waterways everywhere suffered from this new, fast competition, but few more so than the Melton Mowbray and Oakham. The two Companies of Proprietors took vastly differing approaches to the plans of a new railway linking Syston, Melton Mowbray, Oakham. The Melton Mowbray Navigation believed they could struggle on: the Oakham Canal knew their trade was doomed.

1877

Immediately, over half of the Melton Mowbray Navigation’s business was taken away from them: and once the railway was fully complete, trade fell further. In the year up to 1 July 1845, 53,640 tons of goods had passed up the Wreake. Six years later, the total was only 17,087 – barely a third of its previous level. Cost-cutting measures were frantically implemented, as the company skimped on repairs to save money, but the financial position remained perilous.

At this late stage, the Melton Company finally decided to try and sell their waterway. They approached the Loughborough Navigation and Midland Railway in 1862: both refused. The Midland’s answer was still “No” in 1877, at which point the proprietors finally admitted defeat. The act of abandonment was passed that same year, and the Wreake closed as of 1 August. (Legend has it that one boat was unaware of the navigation’s fate, and was forever stranded in Melton Mowbray!)

1997 and beyond

Since then, there has been some navigation on the Wreake – the odd cruiser has pottered up and down for half a mile (recently, much further! Click), and short narrow boat trips have been held in Melton Mowbray itself.

However, as the navigation is river-fed, and all bar one of the lock chambers are still extant, the probability is that by using Transport and Works Orders (as used on the Ashby Canal restoration), all could be restored within a suitable timeframe.

The Oakham Canal, meanwhile, has somewhat merged with the landscape but many sections still retain water, although only the section near Ashwell would be suitable for craft.

The task of resurrecting these waterways should not be underestimated but given time, money and determination, the restoration, particularly in the case of the Melton Mowbray Navigation, is achievable

Restoration Background

In 1948 the UK government nationalised both the railways and the Inland Waterways, and with the infrastructure of both (particularly the waterways) requiring large investment to cope with a massive backlog of repairs, the infant Inland Waterways Association began to campaign to save what was left of this ailing transport system.

By this time, the Melton Mowbray Navigation had been closed for some 71 years, but the plight of the main UK system had aroused interest among the Melton Mowbray populace. Down the years various “friends of the river” type groups had come and gone, before in 1997, MOWS was formed with the specific intention of full restoration for the Melton and to at least get recognition and protection for the line and remains of the Oakham Canal.

The canalised Wreake was never as profitable an undertaking as the nearby Soar Navigation, but Melton’s appetite for Derbyshire coal ensured that enough boats would pass down the Melton Mowbray Navigation (paying tolls in the process) to secure its financial viability. Six years later, this traffic would almost double as 15 more miles of navigable waterway were opened.